Plagodis Geometer Caterpillar

Plagodis sp. fam. Geometridae

Host plant: Not recorded

Dates found: 06 September, 2025

Locations found: Babler State Park, St. Louis County, MO

Notes: Plagodis larvae are well camouflaged to look like woody twigs on their host plants. Their body shape and coloration are not their only tools to use in their adaptive subterfuge. When disturbed, these twig mimics will become rigid instead of attempting to flea, often assuming this position while being handled.

2025 Caterpillar Season – Lace-capped Caterpillar

Snail Kite!

This post is dedicated to my friend and mentor, Godfrey Bourne. Godfrey researched Snail Kites for his Ph.D. work while at the University of Michigan. I remember listening to some of his stories and seeing photographs of this impressive bird of prey. Around 25 years later they were still high on my wish list to find and photograph. Last week, I just happened to have a work trip down to Orlando, Florida. I made sure I had time for a personal day or two and the Snail Kite was the primary species I sought out over all the impressive birds that can be found in the state.

After watching some videos from a well known bird photographer on YouTube, I got the impression that this species might be difficult to find – that these birds are only found in wetlands away from developed areas that take knowledge and special equipment to reach. With my experience last week, I am beginning to think that this photographer’s motive was in selling his high-priced workshops.

Don’t get me wrong, with a current population estimate of approximately 2,000 individuals in Florida, these are not common birds; in fact, they are listed as endangered in the United States. This is primarily due to overdevelopment of wetland habitat in the sunshine state along with mismanagement of these habitats that has led to the decline of apple snails – the Snail Kite’s only food source. Thankfully, this species has a large range across the neotropics, from Mexico and the Caribbean to Southern Brazil. The species as a whole is currently not threatened with extinction.

In two close by areas, only a 30 minute drive from Orlando, I was easily able to find four Snail Kites and watched them for hours in a lake/marsh area that was heavily used by recreating people. Seeing as this is an endangered species, my intention was to give them plenty of room, but I was shocked as I watched people pass by them within just 10 feet or so without the birds seeming to care. On a couple of occasions, I sat down under a shade tree with 50-100 feet between me and the bird and was astounded when they flew closer and closer to me during their foraging. I have always said that any bird photograph taken in Florida should have an asterisk attached due to these birds being so accustomed to people. After just a couple of days experiencing this myself, I still feel this way!

This species numbers in Florida are highly affected by drought conditions and have varied wildly in recent decades. Changing climate patterns are not helping the Snail Kite restoration attempts and I fear for what the next decades may bring. Hopefully they will be as easy for me to find during my next visit to Florida. Thank you for reading this far and I’ll leave you with a few more photos.

-OZB

A Bit of Batting Practice

For the WGNSS Nature Photography Group’s January outing we headed to Carlyle Lake in Illinois. Our primary target was the dam’s spillway. I have had a lot of fun at this location photographing Bonaparte’s Gulls and American White Pelicans during past winters and these species are what we were hoping for on this trip.

Being a spillway with the dam and infrastructure surrounding it, the backgrounds are definitely challenging; however, it is not impossible to handle. The images below showcase one method we could use to handle this situation. With the rising sun at our backs, I noticed the light was hitting these mostly white birds perfectly. By exposing precisely for the whites and a little exposure manipulation in post-processing, it was possible to turn the darker concrete walls of this section of the spillway nearly black, which allows the birds to pop off this background as seen in the images below.

Predicting the movement of birds in a typical winter is difficult and this winter, where seasons have been changing on a daily basis, is pretty much impossible. On top of that, water levels in the lake and spillway channel were a couple feet below normal. The spillway gates were releasing just enough water, which I believe limited the numbers and size of fish falling through. So, it wasn’t surprising that we found almost nothing but Ringed-bill Gulls (RBGU) fishing in the spillway.

Ring-billed Gulls are considered 3-year gulls, meaning that they have a plumage transition for the first three years of their lives before they develop into the typical adult plumage. In addition, there is considerable variation within these years, e.g. a 2 year old gull may look different from a 2.5 year gull. Given I am no expert, I have made some captions with my best guesses on the ages of some of these birds.

Another method of dealing with ugly backgrounds at this location is to focus on the fishing activities or other opportunities where the water will be the background of the image.

Many nature photographers would consider this a bust of a day and would perhaps head back home to watch a meaningless football game. However, I like to look at this as both an opportunity for practice and to potentially learn something new about a species taken for granted and usually ignored. I liken opportunities such as this to batting practice in three ways: 1) It gives you a chance to hone your skills – this is high-speed action photography with challenging backgrounds and dynamic lighting. If you haven’t mastered your camera’s exposure and autofocus settings, you will likely struggle getting the images you envision, 2) It’s a lot of fun! Whatever species you find in a spillway like this, there will likely by plenty of birds fishing, giving plenty of opportunities to capture those fleeting moments, and 3) with a species like the RBGU, you won’t likely come away with anything to brag about. These aren’t eagles or owls or some rare species that will be all the talk on social media.

I really enjoyed watching the gulls catch and position their fish in flight for the head-first swallow. I was fortunate enough to catch this in action in several of my photos – they literally give them a little toss and catch them again so that the head is facing towards their mouth. It was also interesting to watch a few who knew the fish was too large to ingest and subsequently released back to the water.

As I alluded to above, I had a lot of fun shooting these gulls. The feeding opportunities were not as plentiful as I usually find at this location, but by staying alert and ready I came home with some photos that I really like.

Ring-billed Gulls were not the sole fishers we found. We also had several first-year Herring Gulls shown below. Unfortunately these birds did none of their own fishing, but seemed content in attempting to steal the catch from the RBGU.

Thanks for visiting!

-OZB

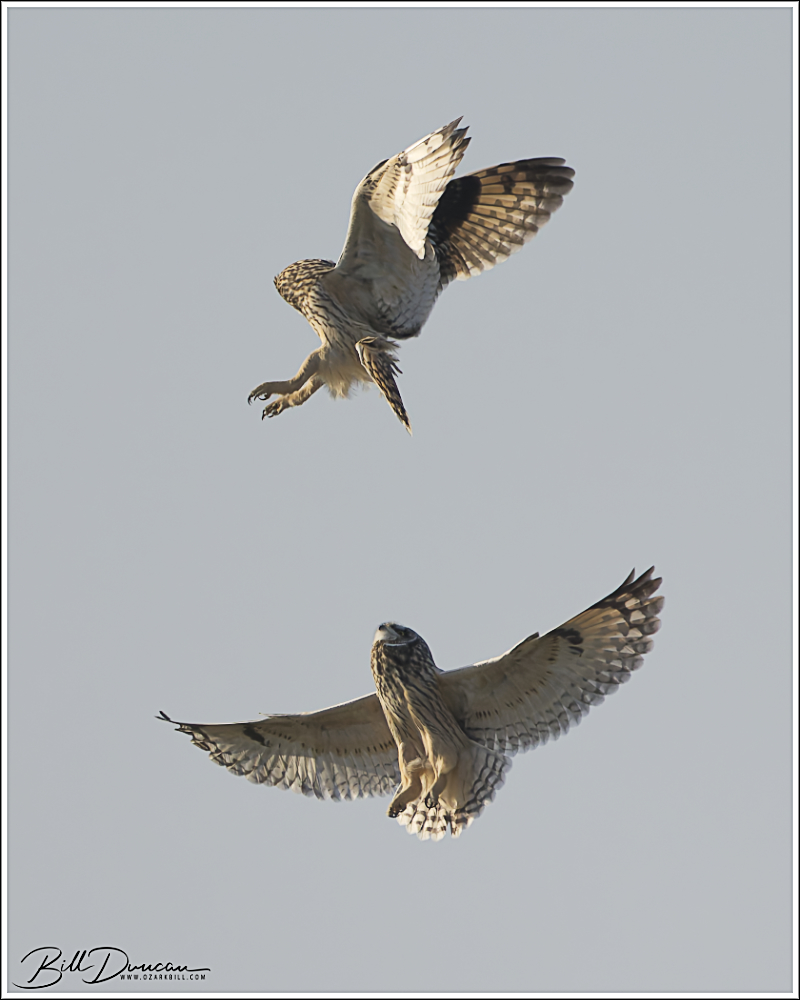

Sharp-shinned Hawk

During a WGNSS Photography Group outing to the Weldon Spring Site Interpretive Center back in November of 2025, we had some nice luck with a Sharp-shined Hawk. My best photos to date of this species.

Mating Harvestmen

During a WGNSS Entomology Group trip in September of last year, we were thrilled to come across a mating pair of Leiobunum vittatum (eastern harvestmen) at Caney Mountain Conservation Area. In some of the photos below, you can see the male handing off his prenuptial gift to the female. Prenuptial gifts are produced by the males and consist of a mix of essential amino acids. Mating behaviors in harvestmen are complex and vary wildly between taxa. Unfortunately, these guys were among thick scrub that made for difficult photography. I tried my best to capture some of this behavior.

2025 Caterpillar Season – Virginia Creeper Sphinx

Virginia Creeper Sphinx

Darapsa myron fam. Sphingidae (Hodges#7885)

Host plant: Found on grape species (Vitis sp.)

Dates found: 31 August, 2025

Locations found: Tyson Research Center, St. Louis County, MO

Notes:

2025 Caterpillar Season – Definite Tussock Moth

Definite Tussock Moth

Orgyia definita fam. Erebidae (Hodges#8314)

Host plant: Found on sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

Dates found: 01 September, 2025

Locations found: Tyson Research Center, St. Louis County, MO

Notes: This species range seems to weirdly stop in extreme eastern Missouri based on official collection records as well as online databases like iNaturalist and BAMONA. I wonder if this species might be more abundant in the state than the data suggests, mainly by the numbers I have found during the past two years.

2025 Caterpillar Season – The Brother

The Brother

Raphia frater fam. Noctuidae (Hodges#9193)

Host plant: black willow (Salix nigra)

Dates found: 16 September, 2025

Locations found: Johnson’s Shut-ins State Park, Reynolds County, MO

Notes: This species ranges over most of the lower 48 United States and southern Canada. It is infrequently found in Missouri.

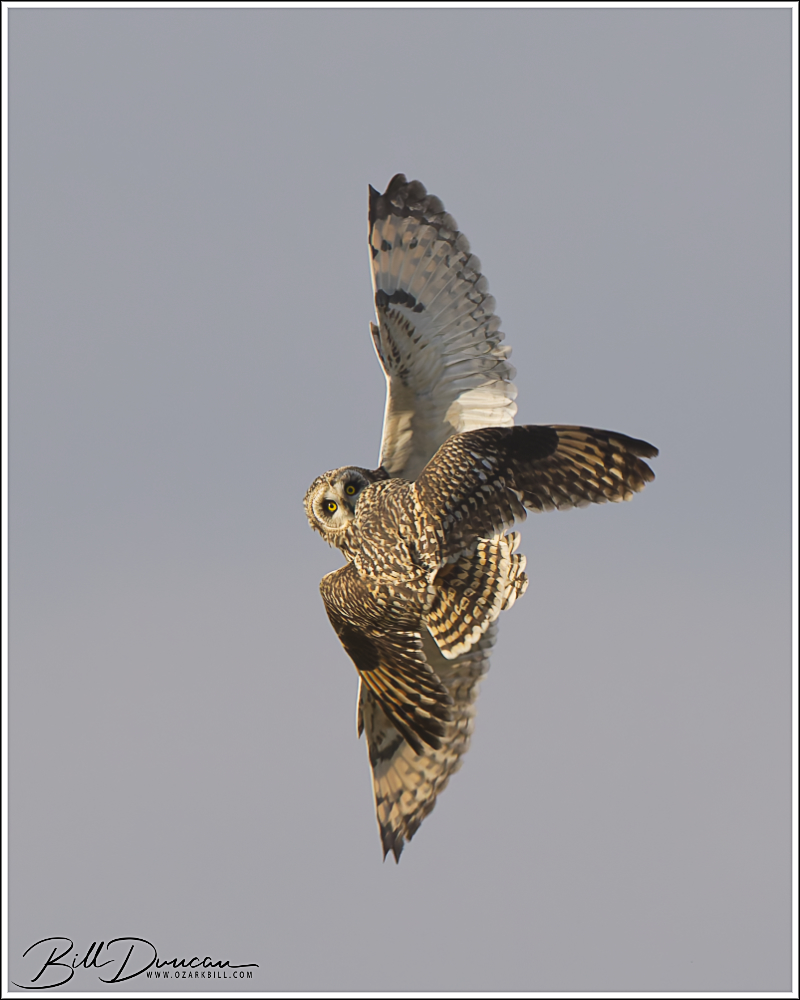

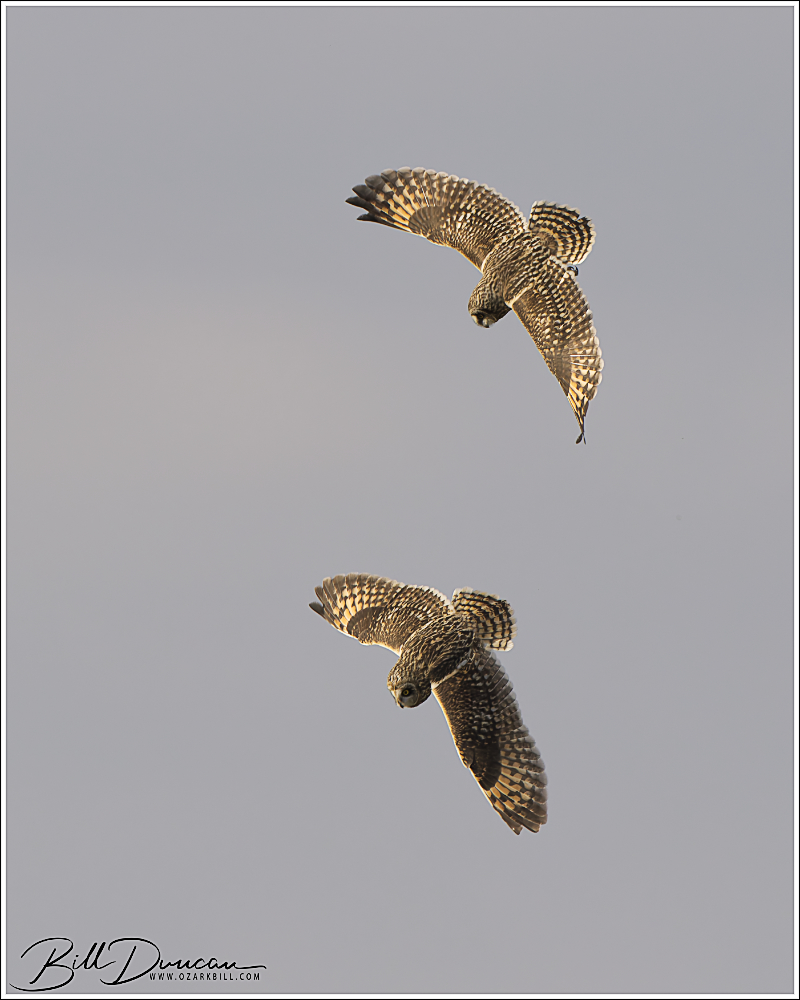

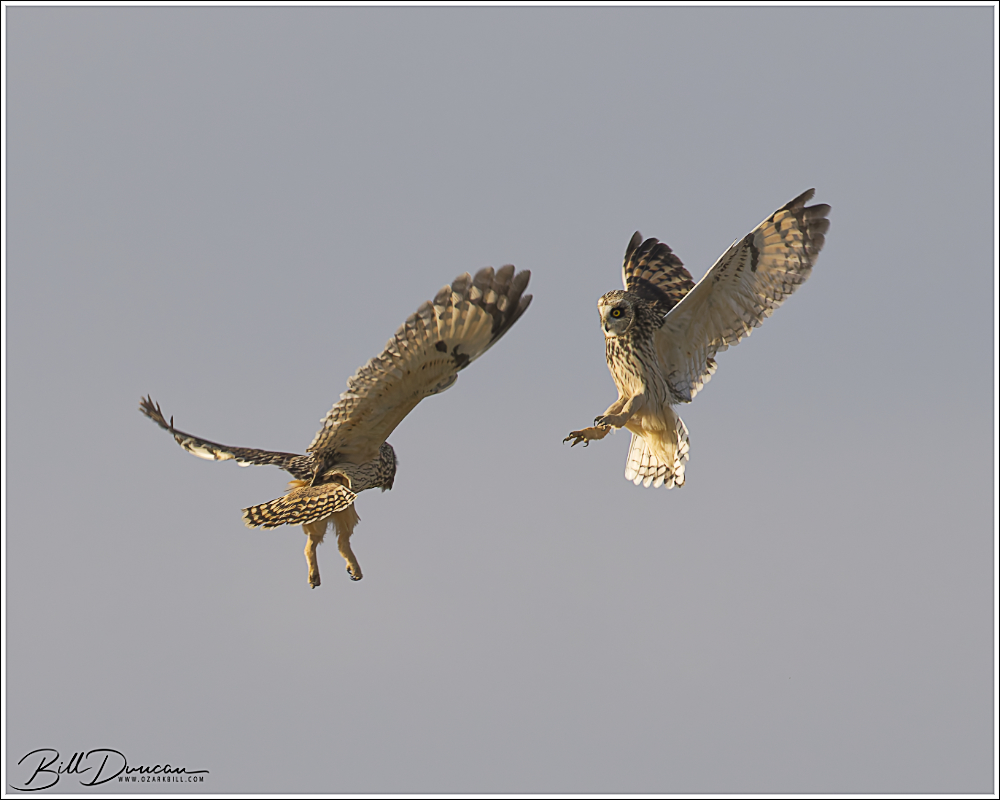

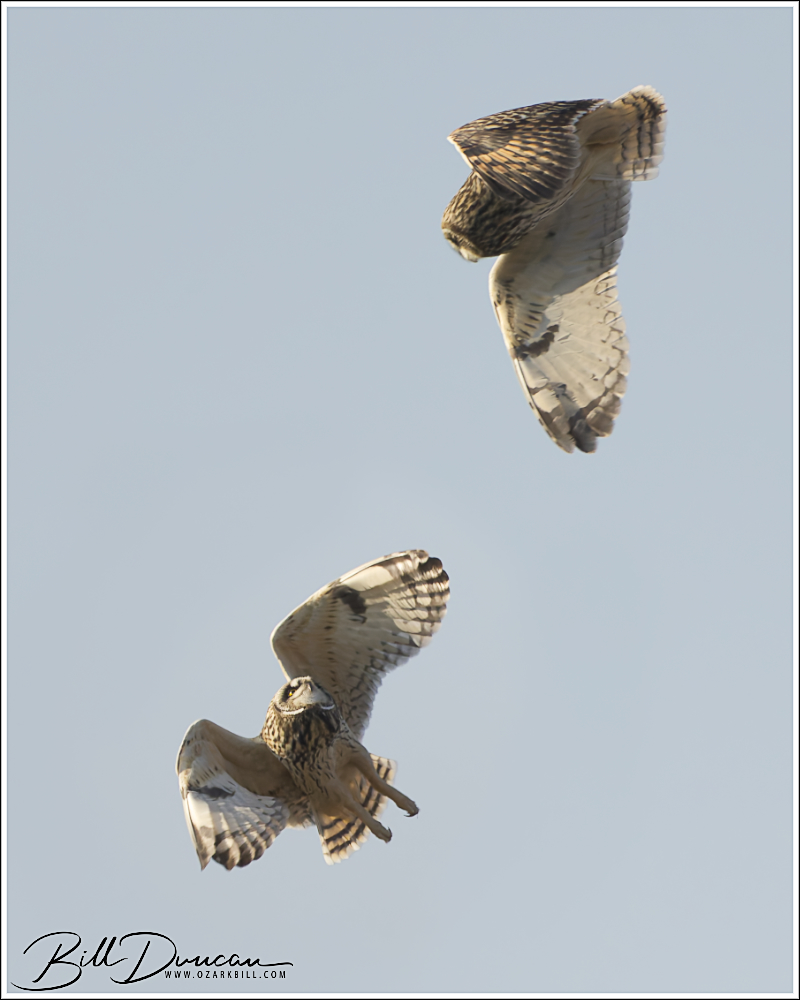

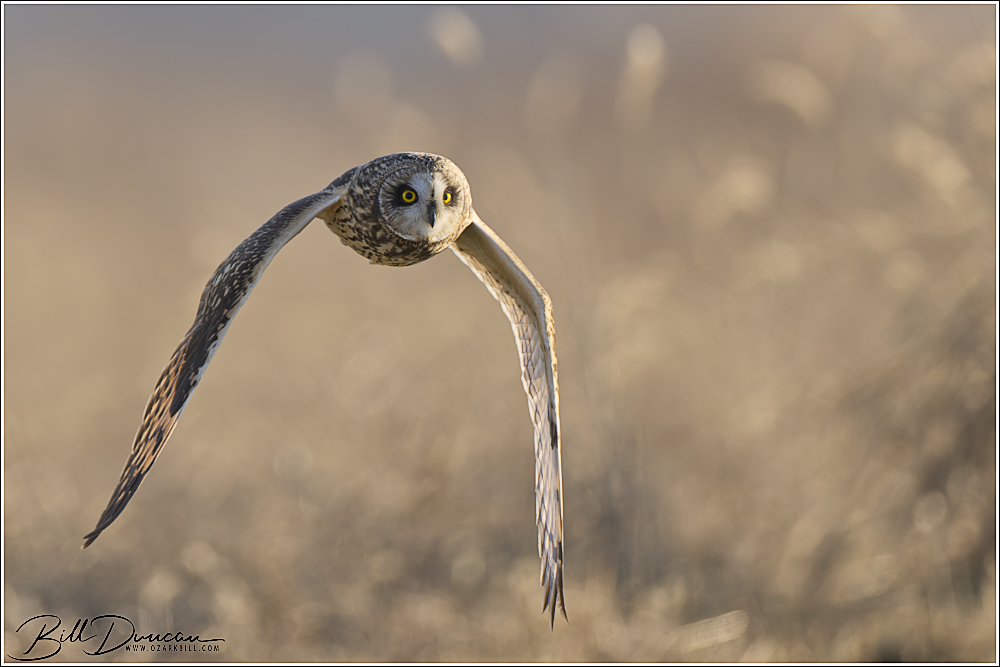

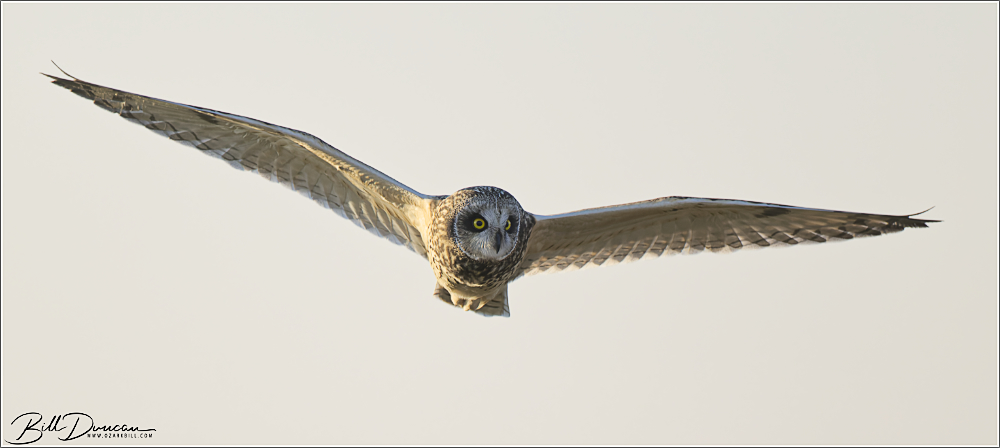

A New Season for Shorties

Here are some of my favorites from a couple trips to a new-to-me Short-eared Owl location in southeastern Illinois.